A wet Tuesday night in May 2010 was the beginning of a journey that I had not anticipated in any way. It began ordinarily enough with me on my trusty bike sweating in the compulsory wet gear fighting the rain and into a headstrong wind. Up a hill to the hospital blinded by the lights of the speeding indifferent oncoming traffic.

Having arrived at the hospital thoroughly soaked and weighing about a stone or more heavier I slowly eased my way out of the dank sweaty gear before entering the consultant's private surgery. I wasn't sure what to expect as I hadn't given the appointment too much consideration.

After introductions and a brief exchange of pleasantries, I was asked to walk up and down the length of his office before sitting opposite him at his desk. Without further ado he quite calmly and directly, with little or no emotion informed me I had Parkinsonism. His unyielding demeanour was momentarily surprised by my lack of reaction - an uncommon outcome I surmised when he delivered said diagnosis to other unfortunate individuals. He countered with the query that I was not showing any emotion or seemed too upset by the verdict, I duly informed him that I was just relieved to know that the symptoms could be traced to some recognised condition and that it was not Alzheimer's, a condition that my mother had been diagnosed with at a fairly young age.

The whole episode probably took no longer than 20 minutes, apart from the referral to a Parkinson's nurse, that was all the information I gleaned from my first visit.

I was to find out subsequently from other patients and from various online forums and support groups that this was typical of their first encounter and diagnosis - (room for improvement, methinks).

On further reflection and discussion with fellow Parkinsons friends, I learned that they had a similar experience. However I now was of the opinion that if the doctor / consultant got emotionally involved in each diagnosis then this would indeed be a very heavy burden for them to bear. In fact each physician has to adopt a professional demeanour in their dealings with patients as the prognosis they often have to present is bad and they then have to witness the reaction of the patient to the diagnosis.

The experience may be more palatable to the patient if there was an immediate follow up service in place managed by an experienced Parkinsons nurse providing some answers to the myriad of questions that the patient might have to allay some of their fears and concerns.

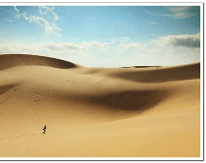

I feel that if you are diagnosed with cancer that you have a basic understanding of what you might expect in the future, however given the range and diversity of symptoms associated with Parkinsons there is a heightened level of fear and uncertainty - my mind conjures up an image of being all alone in a desert full of dunes.